MACABRE BLUFF WITH A DOUBLE BOTTOM

In the expanding, but – if we think of the whole multifarious art scene of today – still limited circle of practitioners of object art, the 30-year-old Amsterdammer Pieter Engels is a striking figure. Not only with what he makes, but much more with his entire performance, aimed at a smooth success, which he has already succeeded in doing. He plays the game of time phenomenon. The rapid career he has made since abandoning his first attempts at painting in the early 1960s and moving into the object genre is striking. The Paris Biennale had already been followed by Documenta in Kassel, and now the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and, just before that, the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven have allocated a number of rooms for his first one-man exhibition of recent work, for objects that this time deal with death, nothingness, the empty, the broken. Not a cheerful event, in other words. While object art often is not, Engels makes it very black, although he does so with a great deal of glamour. And, it seems, with the intention of ridicule and self-mockery, which, however, are largely lost in his solemn, cold bluff with double-bottom tactics and can no longer intrigue or suggest, let alone irritate. He succeeds better with his propagandistic texts than with his objects.

MULTIFACETED TALENT

Progressive modern museums are known to follow the latest developments closely, but that does not mean that every object maker can have a one-man show. Standing out, no matter what, is the first message. And Engels has understood this message extremely well, to respond to it dynamically and with great entrepreneurial drive in a multifaceted manner, whereby he ingeniously combines all kinds of talents – for he has them. Talents which have little or nothing to do with the visual arts, make up the quintessence. He is, in fact, very adept at propagating and advertising himself. And as a builder of his image, he has something genius with a strong business instinct. He brought himself with all that he produces into a N.V. of which he is the director, advertising chief. Public relations officer, copywriter and slogan inventor. In the advertising business he would probably do very well with his tantalizing inventions.

As an image-builder he juggles intelligently, matter-of-factly, elegantly and even very hiply – because he knows what’s going on and what’s fashionable – with paradoxes, relativizations and practical jokes, which do so much better in his writings than with the things he makes, because they quickly become contrived and faint-hearted like sick jokes. Remarkable in all this is his disarming candor, by which he – as must be the intention – makes himself elusive. And it is rather telling that a self-portrait that he once wrote in the Museum Journal, under the pseudonym Simon Es (as he calls himself when he acts as his advertising manager) is called his “opus magnum”. As far as Engels’ aforementioned talents are concerned, a reference to the catalog, which – with glamour – offers a good example of them and in which I also find Engels’ best-successful practical joke with the size, which is due to 48 totally blank pages. But then he himself says – very candidly, see also above – with that: “This has no other reason than to make the catalog considerably thick or to strengthen the non-Engels’ fans in their conviction that it seems more than it is.”

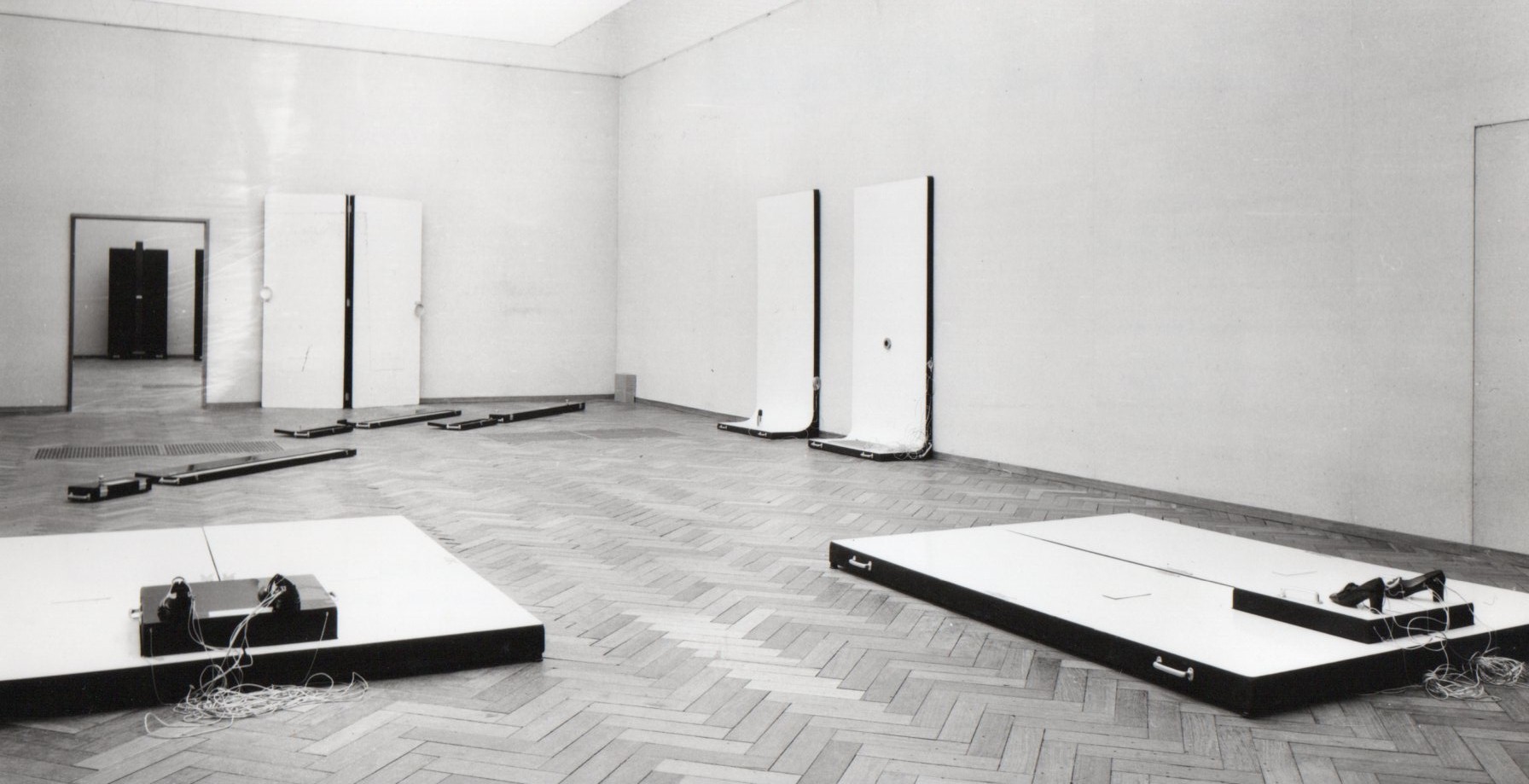

I cannot describe the atmosphere of the exhibition any better than by saying, that it is a loss if you do not have your high sides with you on your walk through the halls of coffins, modern death events” etc. (Engels always titles in English and his expensive prices are converted into dollars). Then there are, among other things, broken window frames and picture frames, the empty back of a modern “art piece” and the “suicide pieces”. Whoever would get the urge to moralize about these suicide installations ( by electrocution) can calmly refrain from doing so. Engels does not like to go over the line of what is appropriate, and these constructions with wears and contact points are apparently intentional, just childish. And as far as the mockery of “modern art pieces” is concerned, you don’t have to see any self-mockery in that, because Engels never calls his objects art, but very matter-of-factly “Products”.

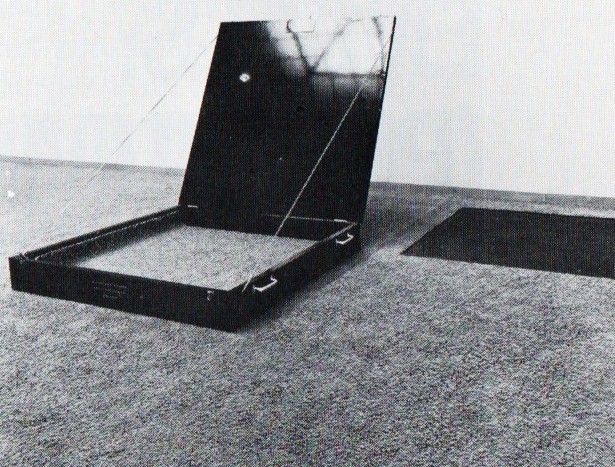

He just wants to be a butterfly that you can’t possibly catch in your net. Everything is possible with him and of course that is what you have to think about what has been said in this paragraph. But what does that matter? What matters here is not what ambiguities he may or may not be hiding in the back of his mind, but what you see and observe. The circular walk ends in the emptiness of a distinguished gray weeping room. A beautiful soundproof carpet on the floor and in the corner a beautifully and perfectly made black box. In it protrudes the piece cut neatly square from the carpet. Prickly Pear may look for a butterfly here.

Finally, what establishes a decisive impression is the glamour of the macabre. The black wood is beautifully polished, the white formica, the aluminum and the chromed knobs, handles and hinges underline the glossy effect even more. With its perfectionism in all respects, Engels does ensure that its glossy effect is not compromised by excess.

In fact, it all adds up to quite a lot. No wonder he stands out and that’s why it’s hard to ignore him in the newspaper.

C. Doelman, 1969. Nieuwe Rotterdamse Courant.