OLAV VELTHUIS works as a journalist for the Volkskrant. Before that he was a post-doc at Colombia University, and an associate professor at the University of Konstanz. Velthuis received his doctorate from Erasmus University Rotterdam in 2002 with a thesis on the art market in Amsterdam and New York.

“With Engels, the economic laws of artistry, which had remained in the wings of art history throughout the centuries, came to the fore in the early 1960s. He made these laws the subject of his art: among other things, in advertising texts that he began to write after brush and paint had been put away.”

Hungry for more success, Engels founded his first company, Engels Products Organization (EPO), in 1964. He decided to get his hair cut, get a suit fitted at a tailor’s, and henceforth go through life as an entrepreneur. Decades before career artists like Jeff Koons and Rob Scholte in the 1980s, or business artists like Seymour Likely and Servaas in the 1990s, Engels brought art, economics and entrepreneurship together.”

When De Wilde had become director of the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum, he invited Engels to one of his so-called Ateliers in 1965. After that – as far as attention was concerned – the game was up. In 1967 he participated in the Biennale in Paris, and in 1968 in the Documenta in Kassel. In 1969 there followed a large solo exhibition at the van Abbemuseum, where Jean Leering had succeeded De Wilde, and later that year another solo exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum. In 1971, Engels participated in Sonsbeek buiten de perken. Almost every Dutch Museum with a budget for purchases of modern art, bought work by the artist. Engels himself made work out of that: Pieter Engels in the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam together with its director looking for a suitable spot to hang this work of art.” (Narcistic Event,1972)

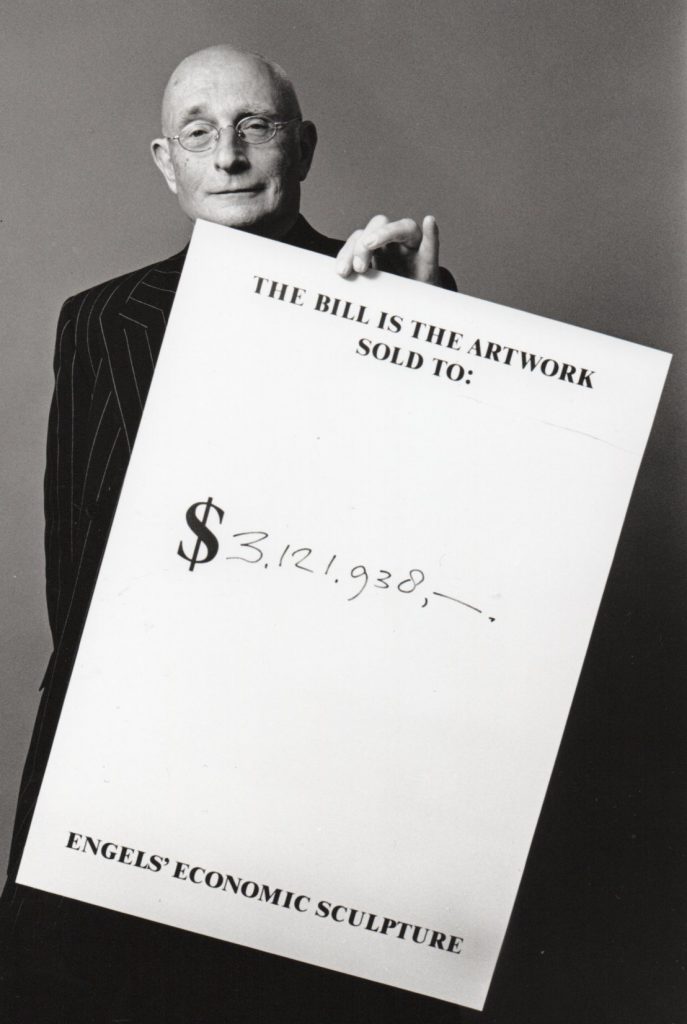

In other words, it is not the artistic value that defines the economic value of a work of art, but the other way around.

Golden Fiction is an echo of the American social critic and economist Thorstein Veblen, who in his unsurpassed Theory of the Leisure Class spoke of ‘pecuniary canons of taste’: our taste is shaped by money. By which he meant to indicate that, certainly when it comes to luxury goods such as art, which are of interest to higher, status-sensitive social classes, basic economic laws do not have to apply at all: if the price goes up, the demand for these goods might increase, not decrease.

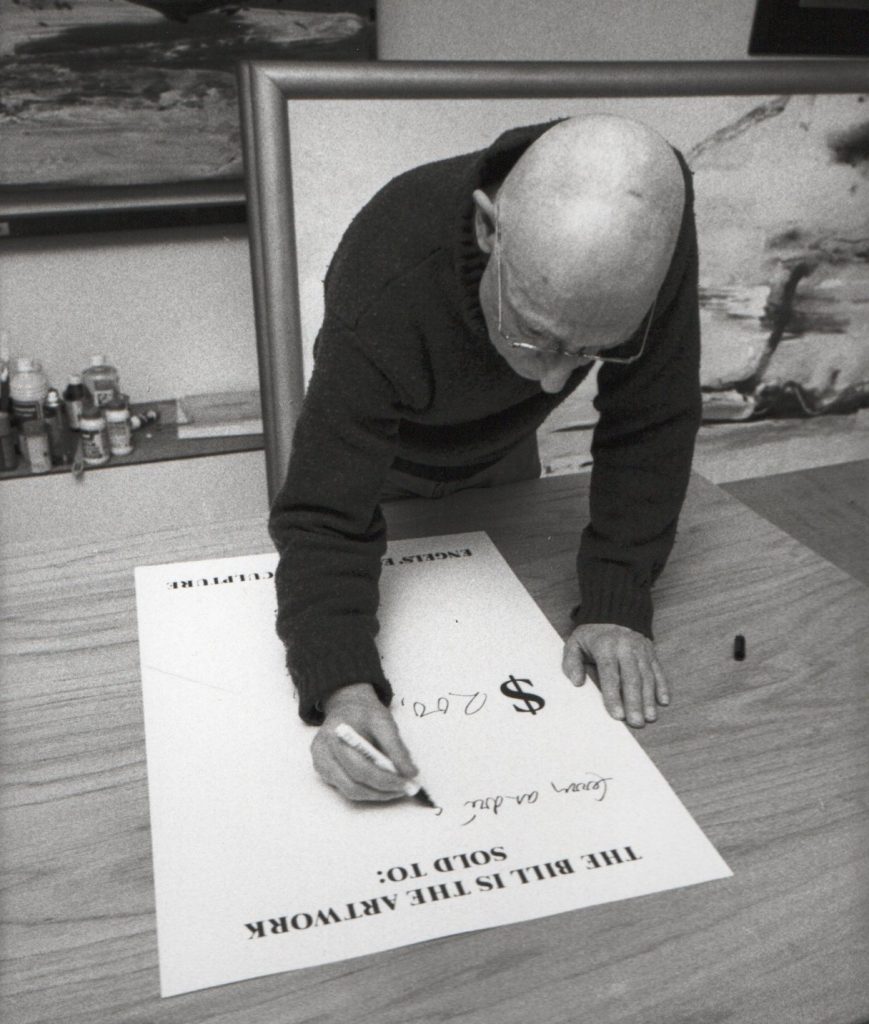

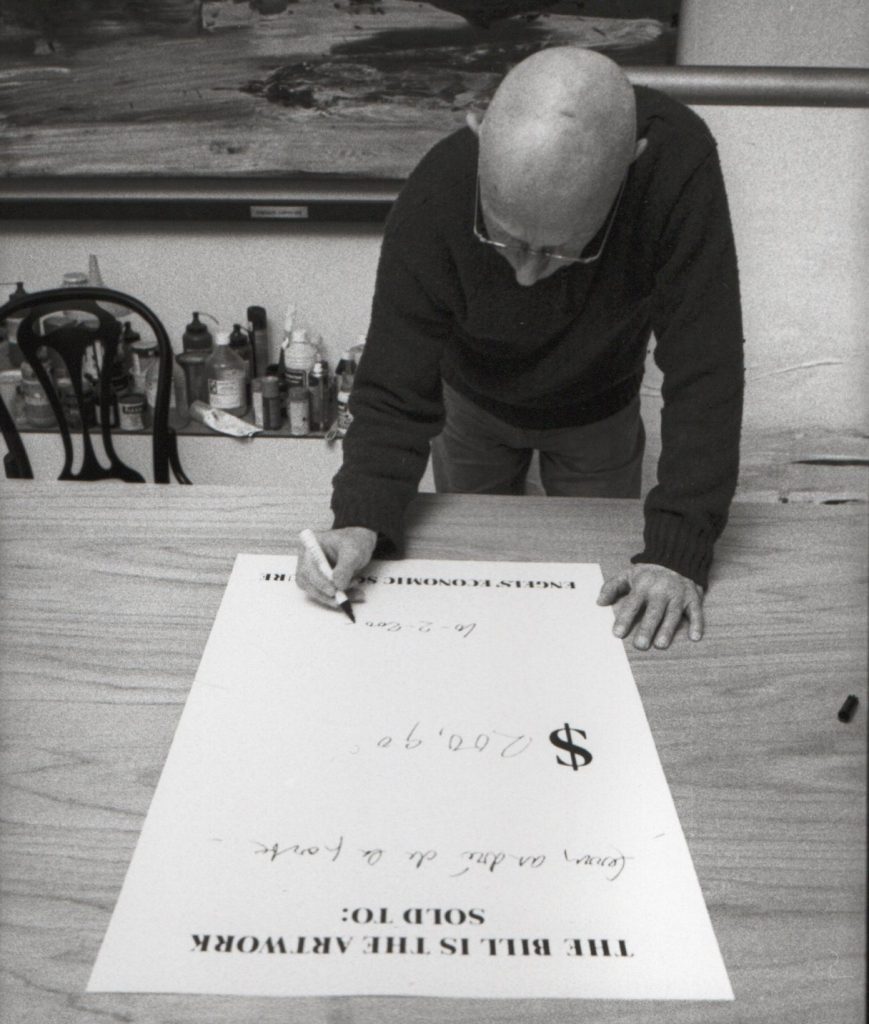

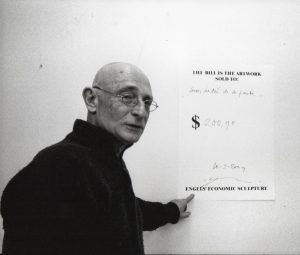

A good twenty years later, Engels says this again. After years of painting, he has returned to a form of conceptual art that he himself calls ‘Economic Sculpture’. In which sculpture refers not only to his own work, but also to the economy as a whole.”

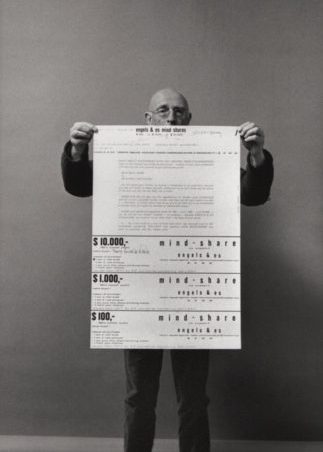

Engels got into the business of banknotes in the 1960s, and in 1977 issued shares, Mind Shares, in denominations of either $10,000, $100,000 or $100.

Each denomination yielded 101% mental gain.

“Although all the artworks were identical, the prices he asked for each work varied considerably. ‘But of course all the prices were different,’ Klein explained with the same feigned naivete as Engels later did. ‘That’s how I look for the real value of the painting.’ That people were indeed willing to pay different amounts for seemingly identical works was proof that the real values really did differ.”

Fotografie Ferry André de la Porte