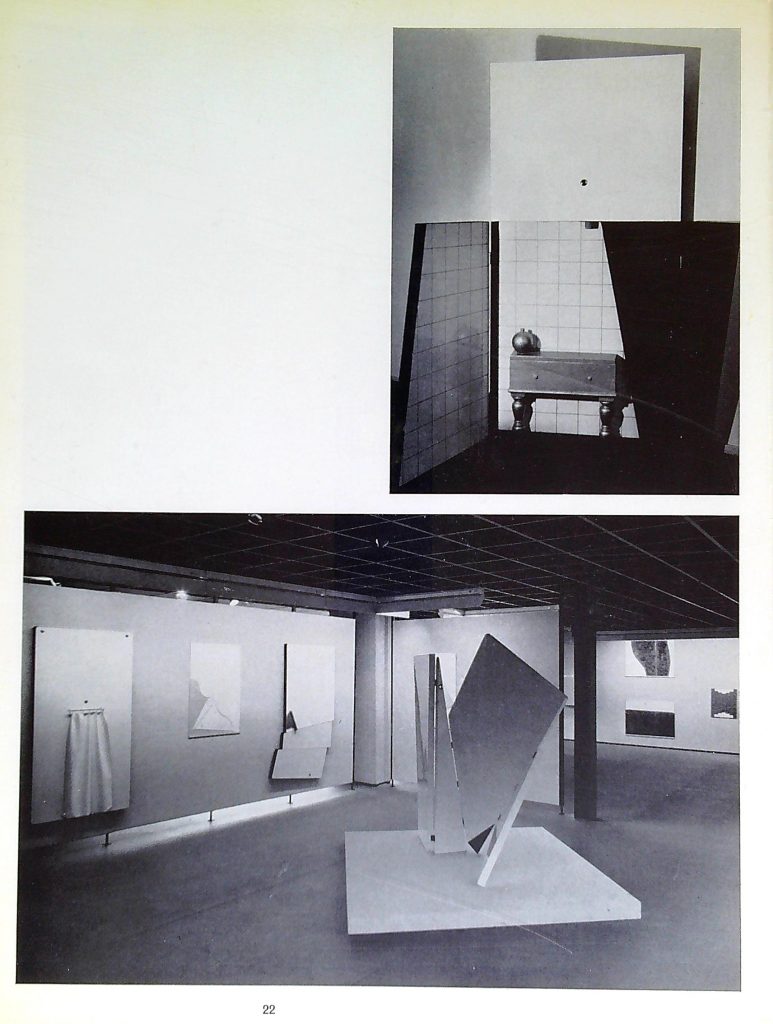

ART MUSEUM Den Haag 1966 SOLO SHOW

PIETER ENGELS IN THE PRINT ROOM

Pieter Engels, one of the most promising young Dutch artists to emerge strongly in recent years, will exhibit at the Gemeentemuseum’s Print Room from August 18 to September 25.

Engels, who became particularly well known in Amsterdam and has already exhibited there several times, wants to move into as many areas of art as possible. He produces wall objects, spatial objects, monotypes and prototypes. He also writes and publishes. His work, “English Products,” as he calls it himself, lacks a clear unified face. Of the work he produced in the last few years, his prototypes, monotypes and spatial objects became particularly well known. The exhibition at the Gemeentemuseum aims to show something of these three facets of his work. The emphasis will be on the monotypes and prototypes, in which a clear trend towards austerity is evident.

Biënnale Parijs / Montreal / San Marino 1967

The Fifth Paris Biennial at Musée & D ‘Art Moderne Paris

ART WITHOUT INCENSE

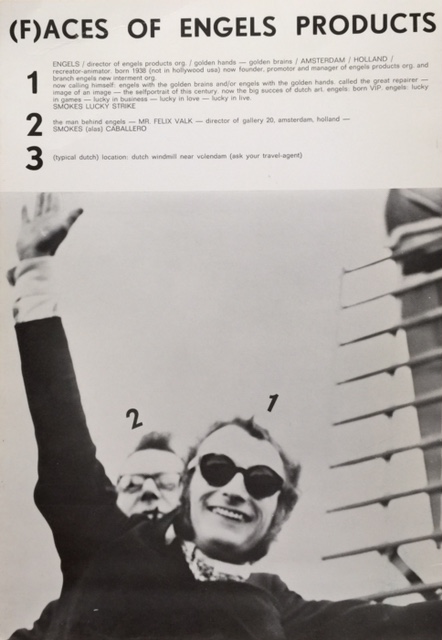

In the Dutch entry, that type of artist is already represented by Pieter Engels, director of Engels Products Organization (EPO). This company also has a showroom: the ,,Engels Room,,. With his golden saw, this artist prepared chairs for a while. The result was then that one can no longer sit on them. Engels notes in the leaflets he publishes on the occasion of his exhibitions, that the Penal Code ultimately consists of a succession of individual words that, otherwise grouped constitute, for example, a pornographic writing. Following modern advertising methods closely, Engels praises himself in his scatterings in a way that defies the courage to exaggerate of any copywriter: ,,What is the reason for Engels’ irresistible rush to the top? A top is Engels by the grace of Engels, that is, Engels is a born top figure. Not for nothing did Engels already formulate: after Engels comes Engels. After Engels comes the avant-garde. Engels is like a natural phenomenon and equally elusive. Engels is really the man with the golden hands, is really the man with the golden brain.’ Engels considers the results of his sawing to be breathtaking and therefore, as a kind of reaction, he now wants to engage in the manufacture of BAD products. (,, There are already so many good works of art being made. ) With this he wants to secure the luxury character of art. English products – last luxury. In a conversation that Herman Swart, director of the Nederlandse Kunst Stichting, and I had with the director of EPO, he was pleased to inform us that he had recently started working on a series of bad portraits of Jules de Corte. Herman Swart smiled brightly at that time, because he could not yet foresee that the steak, which he was going to eat that evening after an elaborate cocktail party at the home of an American millionaire, would be full of sores. This last fact – accompanied by the panicked confusion of three waiters and a maître d’hotel – was the most tragic event of the opening day of the fifth Paris Biennale.

English became the hippest articulate artist at this biennial exhibition, although the outfit of Wim T. Schippers and Daan van Golden certainly also qualified for an honorable mention.

JAN DONIA 1967

KASSEL 1968

Fourth Documenta

IN KASSEL PING-PONG GAME WITH ADMISSIBILITY

” Engels

But the most exemplary of our compatriots for the theme of the whole is Pieter Engels. Indeed, this Documenta, with no more than 1000, partly large and little structured works by 150 artists, is at the same time easier and more difficult to absorb than the previous one. An entire room, for example, is filled with one blocky, black plastic by Bladen (an exhibitor at the Minimal Art exhibition in The Hague). That’s more quickly viewed than a roomful of prints, but perhaps not as readily processed. These things play a game of ping-pong with our receptivity. One has to be constantly aware of what one sees and also examine why the exhibitor does precisely that. He pings, you pong…. or nothing happens. Well, Engels exhibits for example a ,, Modern Landscape” , which consists of nothing at all in a wide frame. At the bottom one can still see the message, No sky, no waves”. And furthermore, on one side of the frame there is a handle, plus a notice board that says: Only for carrying “. So we don’t need to look for an ulterior motive behind this. Another work is a canvas in a frame that has fallen apart halfway. ”Bad constructed canvas” is the name of the thing. Here one can no longer escape the fact that this is indeed not a performance but a thing. During the exhibition, which runs until October 6, a “Besucherschule” is held, something like the educational service of a museum. Engels gives the explainers nice starting points for the whole thing.”

(Dolf Welling, July 13, 1968, Rotterdam News-Journal.)

Stedelijk van Abbemuseum Eindhoven 1969 SOLO SHOW

Engels, with his new products, is suddenly more positive than ever: was he at the time “the great repairer”, then for that repair first of all a destruction was needed, so that he destroyed chairs, albeit very decently, in order to hinge them back together again; or “your car damaged at f 25.- and your car nicely damaged at f 100.-” etc . But I would not quote in this short article. ,, Writing an article about your work is not an art, I say to Pieter Engels, it is a matter of quoting well a lot”, said critic Carel Blotkamp as the sixth introduction to an introduction to the catalogue. There is always quoting, which proves Engels’ quality as a lyricist, but which gives reason to speak of literature in his work; or rather — as if that would be a prerogative predicate — to classify it with literature. The good thing about Engels’ work is that his objects do not need those texts; and that those texts, when it comes down to it, do not need the objects; they are two modes of expression of a witty, cynical, mocking, to me part sinister or morbid ( the latter least) spirit, which do tolerate and complement each other, but never get in the way.

More moderate

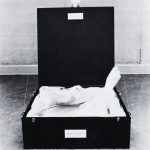

Engels’ contribution to Documenta IV in Kassel was very secular, without text and explanation, and – as I noted at the time – fully up to par with the ( competing ) entry of artists such as Jim Dine, and, in very small context, a prototype of his folded white cardboard in Plexiglas case hangs beautifully in the collection ,, Kunst uit Brabant” in Uden. But of course the show in Eindhoven, which became the first major retrospective of Engels in a museum, also had to bring the image of the EPO organization above all. In this respect, the catalogue and the layout are even more moderate than one might have expected. In fact, one really gets a visual and artistic fix: what Engels does is visually good, captivating, original and with a feeling for handling material that only the best visual artists have. One sees the “lighting-situation fort wo pieces” from 1968, the austere aluminum plates that together form a cool ambience, which surpasses many a work by Zero and for which the neighboring Van Doesburg would have been admired. A terrific chunk of visual inventiveness sticks out in the “electric suicide projects”: anyone who stands on the black formica stage, and puts on the black and white shoes, knows ( and sees) that the tangle of shiny wires connects life and death. Here are things seen and to be seen with such intensity that by being seen they have been made into a work of art, that is to say a thing to look at: the artistic act begins when Engels, somewhere in the Kalverstraat buys precisely those shoes, because he sees in them this death-life situation: objects trouvés are in the best Du Champ tradition. A new pleasant way of ordering to earth’: of everything that our society orders to earth: that is also a broken piece of wood, the ashes of a painting (one by Lucebert, and one by Engels), that is also the Jaguar, which gets a coffin with the outline shapes of the car, padded inside and along the walls lilies, orchids, snapdragons. And one can also luxuriously and artfully electrocute oneself by connecting (for men) between a metal foot grille and a “10,000-volt electric vagina. And even the museum current is brighter than one suspects, so that whoever touches what should not be touched (e.g., the female erotic suicide piece) gets a good thump, to the delight of the attendants, who this time see their work taken over by electricity.

Is it bitter humor? I won’t venture a singular interpretation: Engels’ work is precisely the utter relativization of the univocal approach to things. Those who do so he calls a dogmatist – and perhaps he is right: things are not what they say they are: he tries to outdo that lying, hence his weaving together of figurative and verbal phrases (isn’t this more or less the legal description of the criminal offence of swindling: that will cost me another attempt at compensation for damage to the good name etc. of the EPO, simply because Pieter Engels is so keen on the idea of a lie? of the EPO, simply because Pieter Engels is so fond of sitting behind his antique rolling desk to write joke letters, all on behalf of Simon Es, his sales promoter, who does not exist at all, although colleague Lambert T. thinks he does (a blunder of the greatest order!). The extolling by Simon Es, is the extolling of his own work. This characterizes Engels’ activities: humor and seriousness, and literature and visual art are inseparable with him in an Alfred Jarry-like way, there is no boundary between fantasy and reality. All this makes the Engels show a grandiose exhibition: what he says himself is also true: he is the greatest artist of the Netherlands (What a designation!): he is the most inventive and the most expressive of the entire sarcastic pop-spot guild, but also of the environment-makers and of the objectors. We are curious which work of this show will remain in the museum as a purchase: if I had to choose (I share Blotkamp’s opinion): that delightful piece of businesslikeness with its endearing kitsch elements, that Dutch-proper gleam of polished aluminum, and on which is written:

May 28, 1968 this piece cost:

f 4.344,-

$ 1.200

£ 502,92

D.M. 4,777.30

That’s why it is an art piece. “

(Ton Frenken)

Speech Jean Leering 1969 solo exhibition van Abbemuseum Eindhoven.

Actually there were a number of reasons why I had earlier declined the invitation to open this exhibition:it really is among the exceptions that I open a gallery exhibition with an introductory talk.

To open an exhibition for one gallery creates obligations towards another. And you know how precarious the situation is between museum directors and galleries. But as long as our profession still involves so much work, and on the other hand fortunately so many art dealers still exist or are emerging, there is no beginning. When Engels asked me to open his exhibition, I first said no, and gave as reason that I don’t like all his work. And I think that when you open an exhibition, you have to stand behind the work exhibited. Engels replied that it was about new work, which I did not know, so that I could not judge it until I had seen it. Okay, so we made an agreement, that I would come and see, and that my impression of the new work would decide.

After you put down the phone, you feel that if you’re not careful, you’re already half sold. Sold, yes. You see all the invitation cards, like posters, with all the cool, amiable, but now for years of his “golden hands” known nonsense like: Engels already damages your car from f.25.-; the innocent persiflages on the advertising practices of large producers of luxury – articles. It is only missing, think for a moment, that Engels puts on the poster: “opportunity to open an EPO – show by depositing f. 1,000.- on giro – number so many in favor of EPO”.

But none of this in ordinary contact with Engels, when he calls you, or when you are at his studio. Again, we go quietly to see. Upstairs in his ice-cold attic studio.

I see the new objects, which he has made. And I find them convincing. “But”, I ask him, “what to make of that? Should you even let an exhibition of this kind of thing open with a story about it? If you can ever say of things, that they should speak for themselves, it is these. I could rather imagine opening the exhibition with the playing of some records, or something like that.”

“No,” says Engels, “I want to do it very quietly this time: a normal introduction, and I would like it, if you could do it” . “Yes, but what about that? ! And I look at his objects again. “Now yes” , says Engels, “it doesn’t have to be much.” But by now I understand, that it will be extremely difficult, to say that little. Because compared to these works, any story about material use, about composition, about the how and why of the movable parts, the use of the little banal phrases, processed as transcripts, becomes all too heavy-handed. That challenging question: what to say “, to which I just did not know the answer, made me finally say yes to his invitation.

Engels makes objects.

They are objects, made as objective as possible, as it were. They are made: thus a difference from the ready-mades of Marcel Duchamp, who is called the father of object art. Nor are they alive, as Duchamp’s ready-mades are, through alienation, which gives the object a different quality in perception. But on the other hand, they also have something in common with them, namely that they are as objective as possible. That is, with a minimum of imagination. Their effect must be direct, direct from that, what they ultimately are: things. Self-evident, speaking of themselves. No moving parts, as in Tinguely’s case, whose movement – and the sound produced by it – is nevertheless an ironic comment on our reality, in which the element of imagination is therefore strongly present. Directly, that is how they are made. Made of material that is immediately obvious, of Formica, plastic, chrome-plated fittings and hinges. Almost without poetry, no romance of old materials.

So were they made without feeling? No, because attention was paid to the effect of each of the materials used on the other. For example, the radiance of a single chrome locking knob on a softly glossy white Formica surface. Elementarism?

No, it would be too big a word for it, laden with too much imagination. It’s only about the way those things work; the tension between the materials is not heightened. Just that, what is there, nothing more.

But because of this minimum, because of this artlessness, it works strangely, at least it is strange to surrender to it just like that.

In this attention to the minimum, Engels, without probably knowing it himself, is not alone. Similar phenomena are occurring in America at the moment. Phenomena that in their development run straight through all frameworks of the recognized directions such as Pop- and Opart, and which show a remarkable parallel with a development in European painting between 1880 and 1930. When, around 1948, various American artists such as Pollock, de Kooning and Barnett Newman arrived at their own typically American art form, the action painters stood out the most. In their case, but also in Barnett Newman’s, the spatial aspect is particularly striking, apart from all the other distinguishable characteristics. Pollock’s work builds up layer upon layer, like various networks of spatiality. This is also the case with de Kooning, where the difference in scale of the painted smudges has a spatial effect. Then, around 1955, Jasper Johns paints his flags and targets: with a still tactical technique he paints objects, which are flat for the observer. In other words, there is a tension between the spatial painting method and the psychological moment of the representation, which is experienced as flat.

In 1959 Frank Stella paints his large black paintings, in which the black is subdivided by unpainted, straight, parallel frayed lines, whose pattern emanates from the edges of the painting, from the overall shape of the surface, in other words. In comparison with Jasper Johns, Stella is saying, as it were: there is no need for a psychological moment to make the painting flat. What counts is the surface to be painted itself, of which the dimensions are one of the most decisive factors. That’s why the edges take on such significance. And here one is reminded of the painting by Mondrian from 1919, the composition with grey lines in the Haags Gemeentemuseum, in which Mondrian discovers the edge function of the painting, and stands at the crossroads of composition and structure. But with Frank Stella a different attitude strikes: he sees the painting more as an object, and paints it as such, from which later on the “shaped canvas” logically arises.

Here too there is a minimum. A minimum of means of expression, through which an attempt is made to give the thing as a thing the maximum power of expression. Frank Stella’s position then gives rise to an entire movement. Often it is painters, who increasingly turn to the constructions of objects, from which come the new school of American sculptors like Judd, Bob Morris and Dan Flavin. Their works are very difficult to call sculptures. They are extremely simple, and derive their effect from the tension they evoke in the space for the viewer.

Pieter Engels is one of the few artists, on this side of the ocean, where the same attitude and working method are visible. The fact that he does so in his own unique way, independent of these recent developments in America, may lead us to make a different assessment, which is all too often forced on us by the advertising he conducts himself.

Jean Leering

STEDELIJK MUSEUM AMSTERDAM SOLO EXHIBITION 1969

ENGLISH: SELF-PORTRAIT OF THIS CENTURY

“IN FOUR HALLS of the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum, until April 14, Pieter Engels is the man who holds out to us a ‘, self-portrait of this century’. When he traded his paintbrush for a saw and hammer in 1962, many dismissed his decision with a shrug. Anyone who now sees Engels’ 35 recent works cannot simply pass them by without getting an itchy feeling about our own misery. They are all objects that approach the viewer with a muted aggression. Things are dedicated to death, suicide, burial. There are these very luxurious coffins on display, very important, but true. There is a tremendous seriousness behind these things. Superficially, you can have “fun” at the Stedelijk with Engels. But the thought process is: what a bunch of miserable people we all are. His objects also turn against the prevailing conceptions of art.

He has done this before. Now it seems that Engels is also turning against the public itself. His “projects for suicide pieces” – two pairs of shoes on formica, connected with

electric wires – do not lie. Who wants to be in those shoes?

A quote from the catalog: Pieter Engels calls himself the great restorer”. This means of the normal situations, which he experiences as abnormal. A few years ago he was also the man of the throw-away art. It will be difficult to just throw away his objects in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. But these things do make you realize that the whole world hangs together from old accepted conventions. Engels mocks it, in a cool and almost uninterested way.”

(Frans Duister, March 20, 1969, De Tijd)

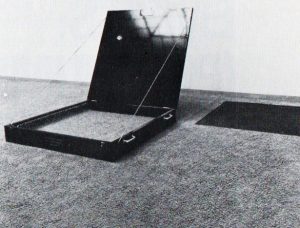

Van Besouw Carpet

“Those who don’t like the loose screwwork on the ground floor of the Stedelijk need only go up the stairs to see some of the best screwed and sawn, nailed and varnished in all of contemporary art. Pieter Engels with the Golden Hands. His show by Engels Products Organization, led by sales promoter Simon Es, has already been excellently presented in the Van Abbe Museum in Eindhoven. New in Amsterdam the “Engels situation: modern death event slumber room for 1.25 m2 , Van Besouw’ Carpet (1402/8).” Personally, I can’t get enough of it. On the third or fourth visit, I encountered one privately, on the far left of the room, where no one goes. He stood watching the visitors. They all do it in the same way. They first feel the soft green carpet with their feet. They experience the transition from parquet to carpet. Then they walk at a controlled pace, slowly, as if reluctantly fulfilling their sad duty, to the black coffin in which the piece of carpet is laid out, cut out of the carpet to the right of the coffin. This is how relatives walk, visiting the grave of a deceased loved one in the cemetery. They stand still for a moment. With exactly that embarrassment that we also undergo in the cemetery. You see them not knowing what to do: pray? grit their teeth? glance at a neighboring grave? Then they turn around and, as if they had finished something, they go back the same way.

,, Yes said the private individual, ,, this is a great work of art by the artist. You feel that he wants to say: it is a lonely adventure, death. And then, compared to the filth below, I think Engels is a gentleman. He does it all wonderfully neat. I praise that in him.”

Pieter Engels says: “There’s a thought that I had a very expensive installation made. I only had the heating turned off in there.” Incidentally, Engels wants to stop doing visual work for now. He feels pinned down after two exhibitions in Eindhoven and in Amsterdam. He feels he has become graspable and he doesn’t want that. He is going to write now. Some books are already ready, new projects are in the pipeline and then in the fall: a new Engels with new projects.”

(Lambert Tegenbosch, Volkskrant 27 March 1969)

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam Print Room 1972 SOLO SHOW

Engels: drawings

from the catalog:

ENGELS: the self-portrait of this century

Exhibition: Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

October – November 1972

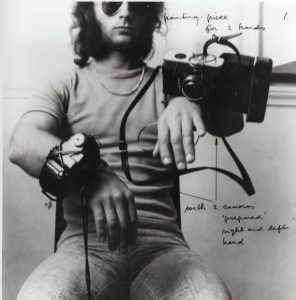

“Pieter Engels’ drawings, which with a few exceptions have never been shown in public, are certainly at first sight of a confusing variety. In this respect there is no difference with the work that he did show in the last ten years, assemblages, prototypes, repaired furniture, letter, curtain and girl’s coat pieces, modern death events, and so on and so forth, and with publications and actions; in those products of head and hand labor, too, there is such a variety that, as a regular visitor to his shows, one would have long since come to the conclusion that there is only one constant in Engels’s work, namely, the avoidance of a constant. In the exhibition now being held, the works do still have in common that they are on paper. Technically, therefore, the variation is limited to that which can be done on paper: there has been painting and drawing with paint, felt pen, pencil and chalk, the drawings have been washed with pieces of paper and photographs pasted on, and inscribed. However, the variation in the type of sculptures created is much greater. Some drawings are designed for objects that have been realized ( e.g. Sound sequence/ sound displacement) or that could have been realized as part of a particular thematic series ( e.g. Modern death event, coffin for a broken chair). Other drawings are studies for projects and events that may or may not have been designed for a special occasion (e.g. Project for a laughing sequence ( laughing trees), originally intended for the event Sonsbeek buiten de perken, while e.g. Sadistic event for a lonesome tree, came about without a specific occasion. Yet others include proposals for projects that are probably impracticable at this point and are therefore called futuristic projects (e.g. Sky event Z/D, no. 4). And then there are also drawings that do not refer to any form of realization outside themselves, but are themselves the outcome of a project ( e.g. Painting piece for 2 hands) or contain an illustrated argument of a theoretical problem (Think event). In addition, the drawings exhibited, as well as Engels’ other works, form a kind of continuous commentary on existing art, especially recent art. From his work there are lines of connection to such far-flung areas as abstract expressionism, the utopian international situationist, zero and fluxus, nouveau realism, pop art, process art and conceptual art. It is going too far to go into these connections, the current exhibition is clear enough: just as Engels’ earlier work paraphrased the heroism of the artist and all his deeds, typical of the art of the fifties, so in his recent work he paraphrases the naturalism that has been appearing in recent years in a new guise in land art and arte povera. That Engels starts from existing art is also evident in the way he has recorded his comments on the patient paper. Some drawings have the prosaic appearance of a piece of conceptual art (e.g. Reverse event, monument for a monument A/A no. 1). Other drawings have an impressionistic touch (e.g., landscape beautiful) ( painter beautiful) = (art is beautiful) or are sketched smoothly with felt-tip pen in a vein that architects and interior designers use for their future dreams ( e.g., Sky event Z/D no. 4), and still others are done with a virtuosity a la Oldenburg ( e.g., Comfortable situation for a lonesome tree). Engels’ drawings contain technically and substantively legion of quotations. Quotation is a practice currently practiced by many artists (in the Netherlands one could mention Reinier Lucassen, Sipke Huisman and Ger van Elk, taking all the differences into account) but in my opinion Engels distinguishes himself from the artists mentioned by the fact that in his case a quotation almost always includes a negation or an inversion. His activity as an artist seems to be aimed at undermining the concept of style. Style in the sense of fixed mode of expression, use of fixed means and of a fixed repertoire of images, has been a natural attribute of the artist since the Renaissance, and Engels recognizes in it the danger of mistaking style for personality and consequence for quality, a danger that is greater than ever in the twentieth century because of the commercial need to consolidate a style once acquired. Engels’ weapon is the quotation, the paraphrase, sometimes the parody; with his work he is the capricious baroque counterpart of someone like the American painter Ad Reinhardt, who attacked the clichéd style from a purist view of art. Engels’ endeavor is akin to professional suicide, given the central place style occupies in the Western concept of art, and one might ask what remains to be done for an artist who denies the value of style. English’s answer to that question, as his work attests, is: to make art out of denial.”

Carel Blotkamp

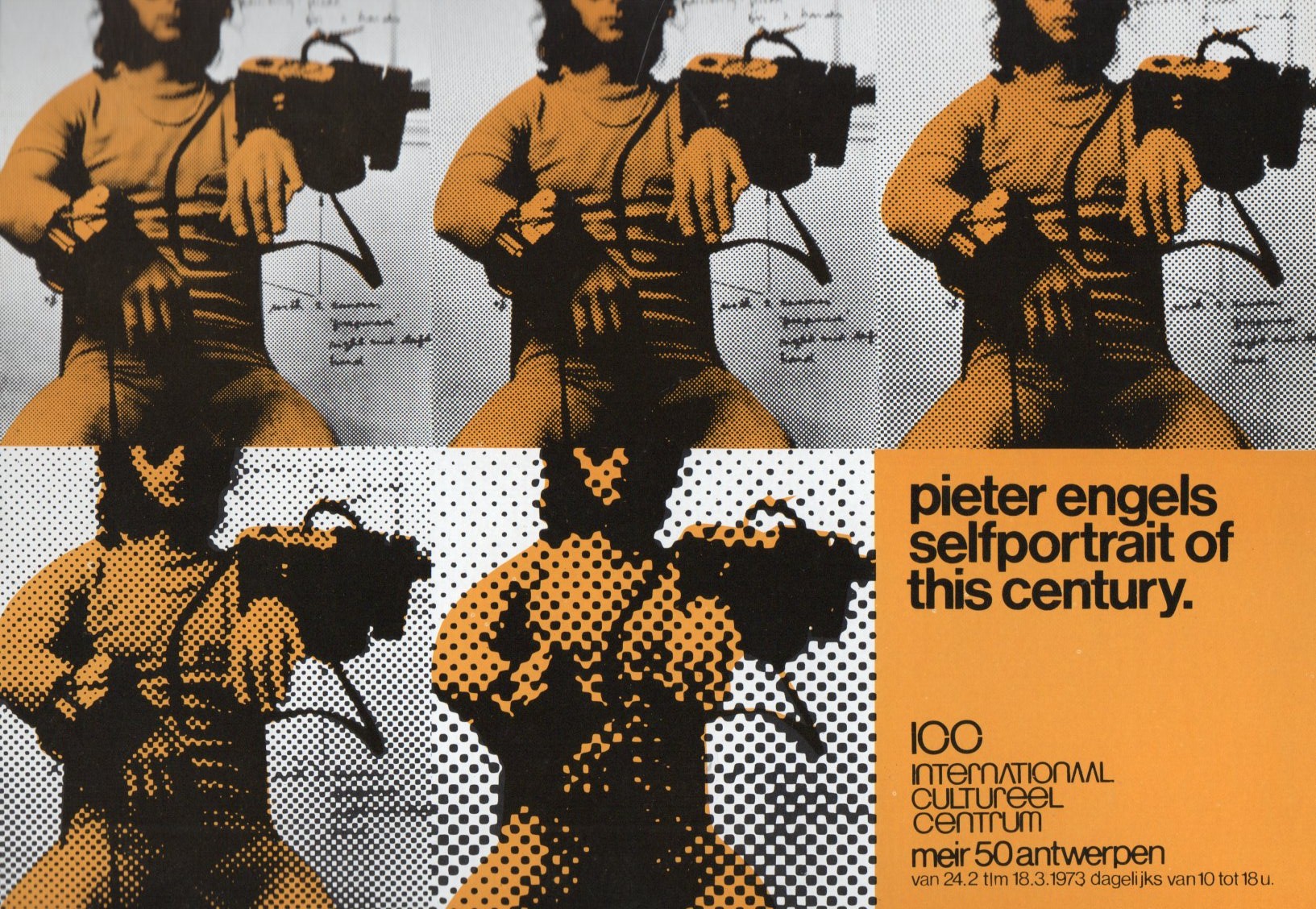

INTERNATIONAAL CULTUREEL CENTRUM ICC ANTWERPEN 1973

ICC: smile or walk away

PIETER ENGELS

WHO ARE YOU?

“Aggressive, sarcastic, confusing, Pieter Engels both incarnates all the traits of an alternative young art that attacks everything, and first and foremost himself. He makes art about art in a way that is destructive and liberating. And is it even art? Who is artist? Engels answers with visual paradoxes and with boutades-in-the-space. There are only two responses possible: smile or walk away furious. May I recommend the former?

If art exists only where individual emotions are transferred and where the Eternal Human is probed, then Pieter Engels amuses himself at best with cerebral jokes; if art is also allowed to have a disorienting function, to undermine sanctified views, to affect old viewing habits, then it must be acknowledged that Engels does this excellently and each time even brilliantly. Don’t expect him to move; but be prepared for shocking and (therefore) mind-blowing states of affairs. This warning shows that I find it useful when fixed habits and traditional certainties are questioned. That I am happy to call a spiritual questioning, a subtle disquieting art, when the forms in which that happens possess communicative power. And that, by the way, the granting or not of the predicate art is one of those fixed customs which is the first to be called into question here.

IRONIE

The relativizing attitude that Engels adopts applies to both contemporary and ancient art, both the maker of that art and the consumer. Statements like *This object costs…. (here a fabulous amount)… Therefore it is a work of art” denounce both the snobbery of collectors and the insane prices on the international art market. (The prices that Engels himself asks for the products are not that low either, by the way. Like many other socially critical artists, he benefits from the system he denounces).

The cult of the uniquely deified work of art, as practiced in the great museums, ridicules Engels with a series of empty frames, all bearing a plate with the name of the painting that is not in it. But art as a mass product and the current craze of the ” multiples ” also have to go. Engels also set up a number of imaginary small companies in Amsterdam, of which he was the director and the entire staff, and which could deliver any “work of art” to order. Other stylistic principles that are often used are “negation”, which suggests something that is not there: “room for no chair”, “room for no corner”; “probability”: “lock to lock up a recalcitrant work of art”, “gate to allow a work of art on wheels to pass through”. And then there are quite a few ” “narcissistic” actions, in which Engels portrays himself, busy concentrating, painting, or drawing his tribal image next to that of Rembrandt. Vanity and self-mockery keep each other in (unstable) balance here. His exhibition at the ICC goes by the title ” Selfportrait of this century *: (Engels uses only English) in fact, of course, it is first and foremost a self-portrait of the artist.

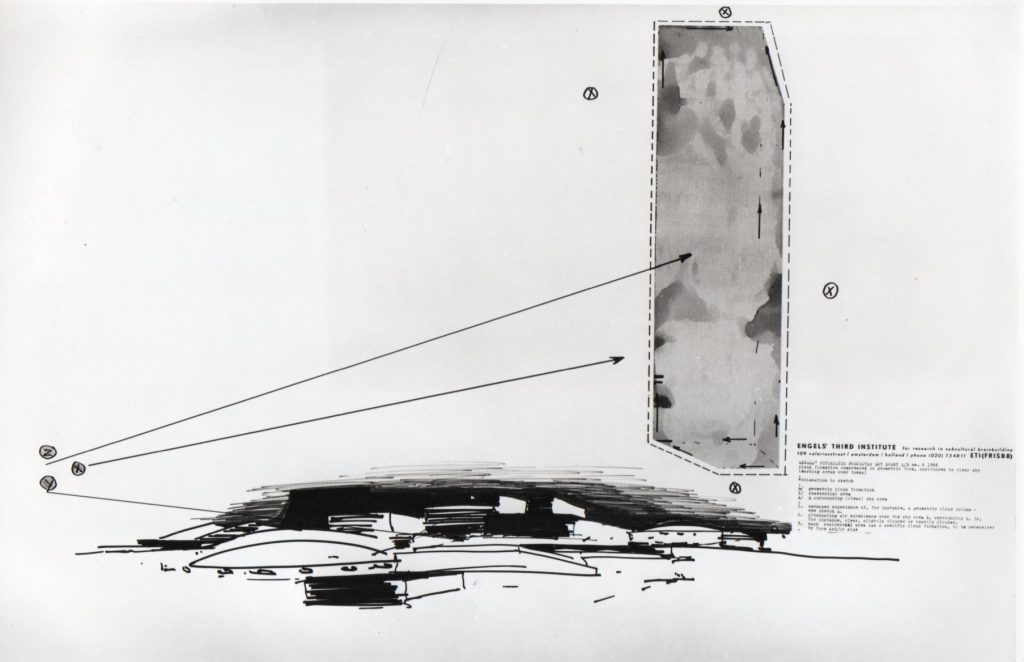

ARTFICTION

And though it goes directly against his intentions, of course – his exhibitionism is a hiding – it does raise the question of the identity of that artist. What kind of person is he, beyond vain, witty, cynical? Pieter Engels, who are you? It is possible to discover a less conspicuous aspect in his production, in which a romantic imagination is expressed and a sense of nature, which disguises itself in crazy projects but must therefore be no less deep and pure. Examples are the “sky-events” with floating trees and compressed clouds, the “geographic event” in which water from different seas is packed and sent to other parts of the world, and also some beautiful landscape drawings. Since direct nature lyricism has become unbearable, such detours are the only option for those who cannot forget nature, and are too intelligent to use worn-out and worn-out clichés. After all, it is now the case that we alibis have alibis if we still want to say something about trees, air or water, and not make ourselves look ridiculous. these alibis then preferably weigh as technical, as science fiction-like as possible. They may also be macabre, such as Engels’ “coffin for drowned water”, which now has an ecological undertone, as do the “landscape amputations” for that matter – although environmental concerns were certainly not his intention. Or was it? His tape recording of street noise, recorded on different floors of a house in Amsterdam, also indicates sensitivity to the liveability of the environment.

NEO-DADA

Of course, there is a good dose of dada in Engels’ attitude, and the comparison with Marcel Duchamp is obvious: Duchamp, who so radically challenged art that he ceased all creative production in the second half of his life, and Engels, who promised to do the same if people gave him 25 million guilders. The difference with Duchamp is that Engels, out of his doubt of the meaning of all art itself, continues to make art to the point of absurdity. That absurdity inspires him and he drives it to the grotesque. According to reviews in the Netherlands, many people are irritated by this. It only proves that he effectively disturbs the fixed pattern of perception and that he therefore fulfils a useful function in the fight against yellowing and aging.”

(MARC CALLEWAERT)

Museum Boymans van Beuningen Rotterdam 1975 SOLO SHOW

“Pieter Engels, the Amsterdam artist has versatile activities, temporary and timeless, but in his judgment all equally important. In his art he cultivates and criticizes himself and society, he relativizes conditions and so-called dogmas, undermines conventional formulas. He founds institutions that are dissolved shortly after their creation to pass into others. These are peculiar self-projections in a society that is suffocatingly full of institutions and which he more or less ambiguously parodies by including himself. Thus he is now at his fourth institution: ‘Engels’ Genesis Foundation’ . Preceded in 1964: the ‘Engels Product Organization’; in 1967 ‘The Engels New Interment Organization’; in 1969 ‘Engels Third Institute for Research in Subcultural Brainbuilding’! In the context of these fictional enterprises, he produced a considerable written ouvre. His Statements, under-statements, slogans, metaphors, persiflages are an integral part of his ‘ambient art’. The objects, environnements, preformances, drawings, photographs are the visualized representations of his anti-conformist, satyrical, literary and surrealist mindset. ‘ What Engels does is too much to mention’! “

Renilde Hammacher – van den Brande, Chief Curator of Modern Art Museum Boymans van Beuningen, ( 1962 to 1978).

PHOTOGRAPHY DICK WOLTERS

ENGLISH: SELFPORTRAIT OF THIS CENTURY

“EPO-EPOCHE IN BOYMANS

The packed auditorium of Boymans was earth dark while Pieter Engels painted and framed the canvas in ten minutes, which he then donated to the Rotterdam museum. It is called ,,The Spectators”, but the coffin must remain closed until the end of time. That’s the absurdist Engels all over. Until 14 July he has a major exhibition in Boymans. Among the lenders in the catalog, a Simon Es is also listed. You will never meet that man. He is a creation of Engels, who bills himself as an entrepreneur. Pieter heads his “English Products” company which does EPO art and has the publicity handled by Simon Es. Since the 1960s, Engels’ work includes various objects and publications. It is also a performance, a public behavior. With all that, he reacts to what is going on in art and further in society. He parodies business, also that in art. He offers some feigned aggression for sale. The catalog gives an excellent picture of that activity, but it does require knowledge of the English language. It is, after all, about Engels. The exhibition is stimulating. Engels did make some nice things and that’s a bonus. But he is above all a man of ideas, and in addition to lame jokes, there are also costly ideas. He is a laughing critic, who forbids an Amsterdam art critic to write about him on pain of a fine of f 10,000.

LITERATOR

Pieter can also do very well in his mother tongue. He has enriched our literary world with some little-known contributions. In the sixties he spent some time on death. Among other things he created a black coffin for 10.2 liters of drowned water.

“Death,” he told us these days, “is the most exciting moment you have ahead of you.” He doesn’t believe in death, by the way. “You couldn’t feel present now if there was a death later.” In an empty frame, Engels shows “The Emperor’s Clothes,” seemingly getting in the way of people who find abstract or other art they don’t understand to be just “fake. If we were to take Engels to task about this, he would firmly refer us to Simon Es. Engels hides behind his public behavior and with the Pieter behind “Engels with the golden hands” we have nothing to do in public. This is addressed to the amateur psychologists, who will receive strong incentives at the exhibition.”(Dolf Welling, Rotterdams Nieuwsblad and Haagse Courant,1977)

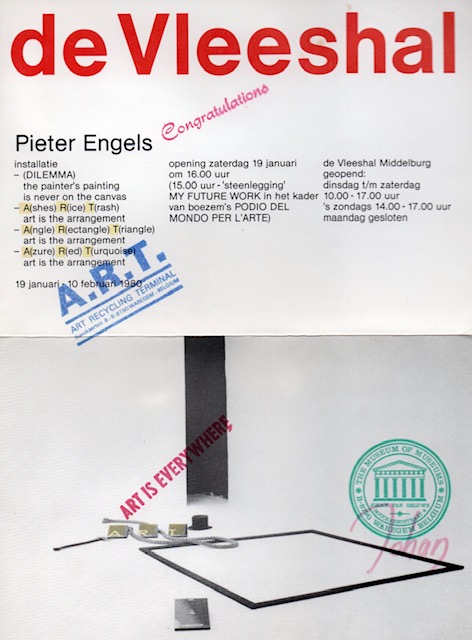

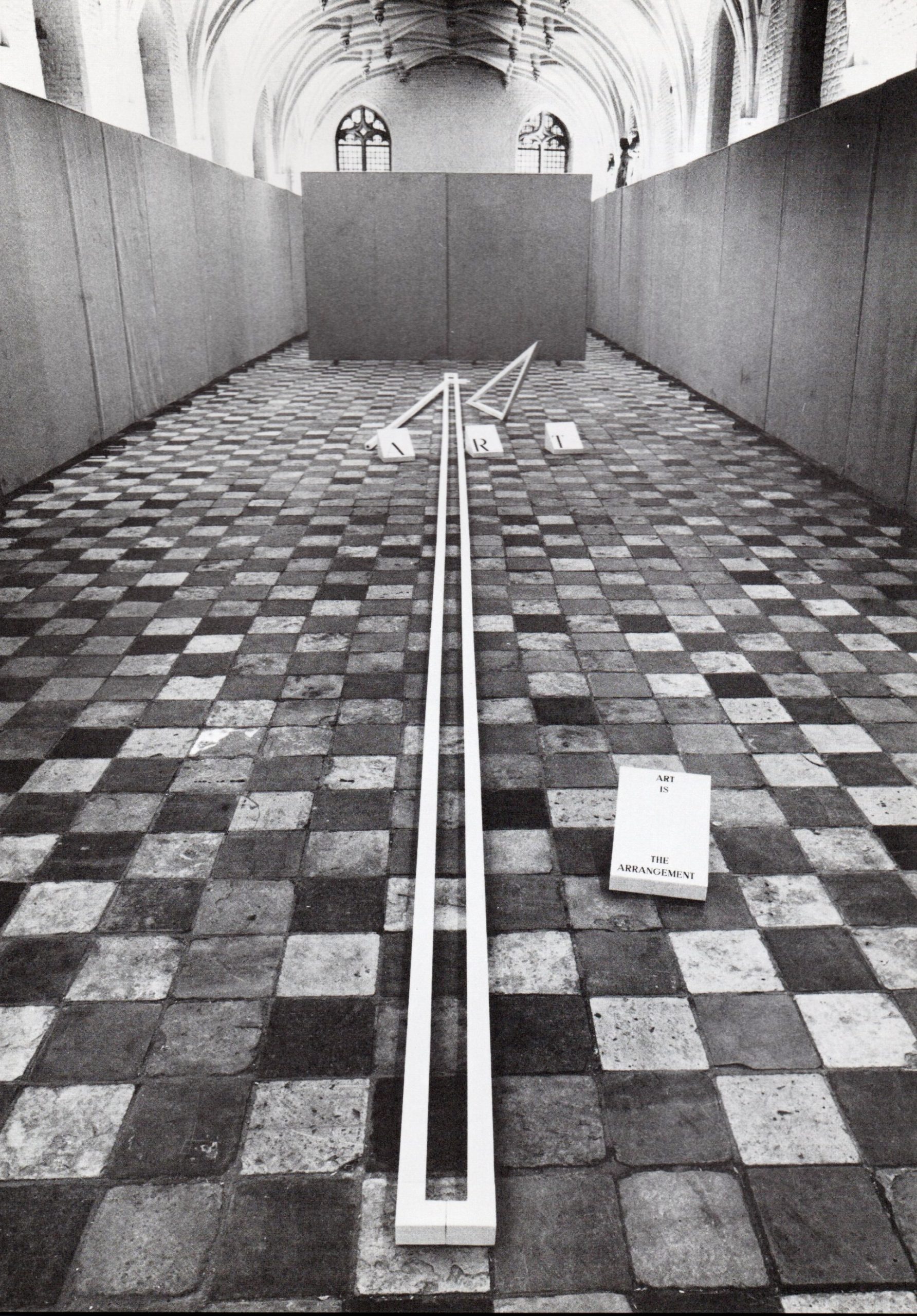

DE VLEESHAL MIDDELBURG 1980

Art is The Arrangement: AZURE, RED, TURQOUISE

Art is The Arrangement: ASHES, RICE, TRASH.

DILEMMA: THE PAINTERS PAINTING IS NEVER ON THE CANVAS

MY FUTURE WORK : what I will sign again whit my enclosed blood on 3 dec. 2579 (PODIO DEL MONDO PER L’ARTE).

Pieter Engels, recreator-animator, is showing one installation consisting of four elements on the theme of ART at Middelburg’s Vleeshal. ART could stand for ‘art ‘ as it stands here – in Engels’ view – for ‘arrangement.’

‘Art is the arrangement ‘ is Engels’ motto. He arranges, at his will, art and society: in a context that assigns powerful values to relativity and irony. Anyone who has previously come into contact with Engels and his work will not be talking about entirely new principles. In all prior activities from painting and drawing to the objects, audio projects, texts, actions and the January 19 stone-laying at Boezem’s Podio del Mondo per L’Arte, irony and the sometimes somewhat parodic relativization have been given rich opportunities.

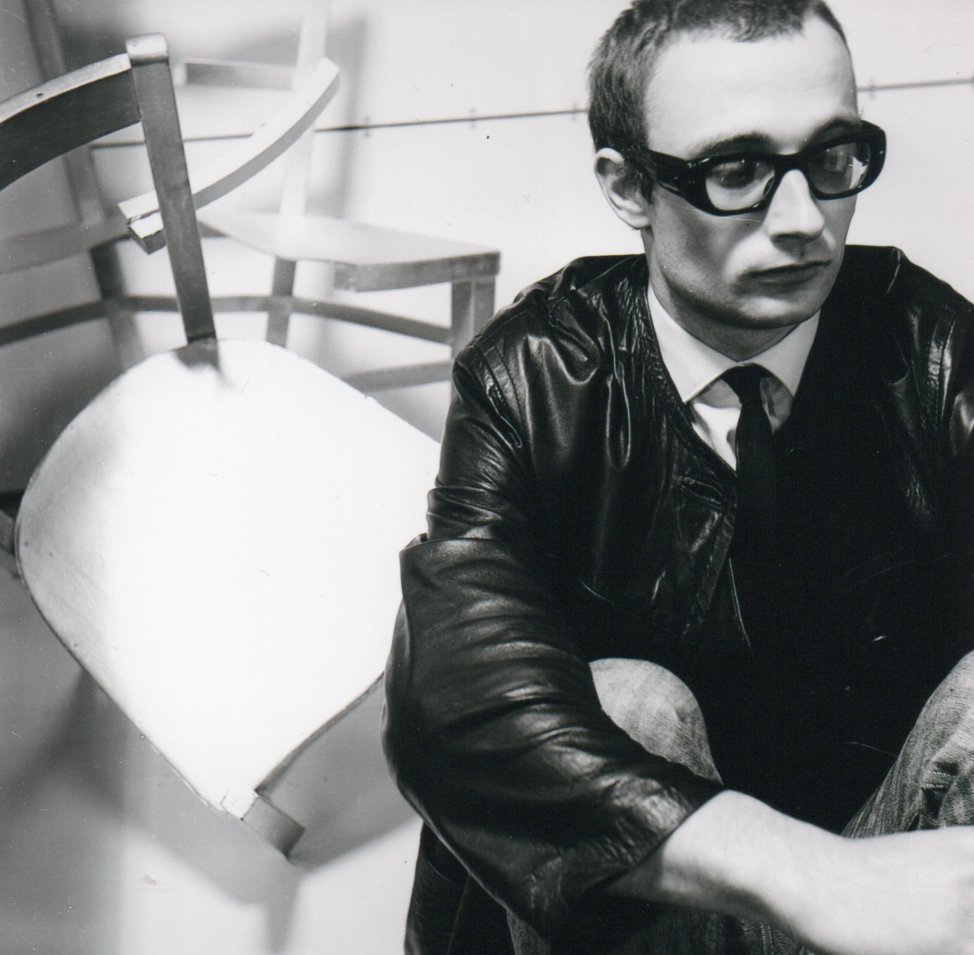

Pieter Engels (b. 1938) is one of the few who already in the early sixties gave adequate shape to what has been called ‘the new artist ‘. Every trace of the ‘artiste peintre ‘ old style’ has been erased (or at least absent). The sickening penchant for outward distinction between artist and people no longer exists. The mindless Montmartre type that so loved to derive powers from meager meals, ropey shoes, pub tales, crumbly dumplings and fat necks, has been consigned’ to the dustbin of the kind of history that determines its own resting place. Pieter Engels’ presentation has nothing to do with any gulf between “artist ‘ and “society. He does not tarry on sacred mountains, does not know the entrance to ivory towers and does not want to co-shine in crystal palaces. He is part of society and participates in the developments that are called ‘ society.’ He no longer lets people trot for him, but trots himself. His ‘ art ‘ has become ‘ project ‘. Engels develops, animates, produces and sells his fabrications: the artist as the linchpin of ‘entrepreneurial production’. He develops, animates, produces and sells mainly himself, irony included. Thus emerges the type of artist who is at the beginning and at the end of a production line, contemporary, without reminiscences of the kind who, in the tiresome demands of a cultivated appearance, forgot the core. What is particularly striking in his manner of project development is his denial of detours. A preference for the direct?

Pieter Engels: ,, Everything has to happen as directly as possible. When the concept, the idea, is worked out, everything must be there. When I bring that out I am no longer needed. Then only the outcome of the work and the , people who take note of it exist. Something that cannot be clear in itself should not be shown. Then you deceptively soon arrive at dim states, a little dark romanticism, those performance-like situations where the story is filled in afterwards. That really shouldn’t be able to continue. The point should be earlier, the concept should be clear and so should the elaboration. Smokescreens should be unnecessary. There are things that come at you. They are there and you can say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to them. Then at least you have done something with it. Then you may have followed the intentions of the concept, the starting point. That starting point must be good, must be virtuous, even if you wanted to make and show an orthodox still life. There must be thinking. Worked from a thinking that controls the matter. I juxtapose thinking. I arrange, I group, I consider, discard, preserve and I present a final conclusion. It must be clear and not give rise to misunderstandings”.

Style

Engels has regularly been accused of lacking a distinctive style. Pieter Engels: off the cuff. Yes that is said. I refuse to have a style of my own. I do what my thinking makes me do. Connection is always there, of course.

Everything originated anyway in the one jungle that is my brain. So the tangents are there. But a style of my own, no rather not. That used to be considered a very great thing, everything was allowed to be terrible and thoughtless as long as it had its own style. What you say now, about that irony, that in itself will be correct. But it is an irony with a double bottom. Again, that’s where I come in. I am also a little bit the declarer for myself. Those who want to decondition, who want to direct people differently, to cut off development if necessary, let that happen to themselves. That is what I call a double bottom. ”

The director of English Products Organization made little mistake about his approach. For example, going back to those early sixties, he handed out fun airline trips, refrigerators and mixers when purchasing his manufactures, to the bitter fury of black-scribes and effusive tributes from white-makers.

So he founded the English New Interment Organization, which offered to bury people, animals and things in a somewhat more festive and lighthearted way than the usual, or to cast them as living room objects in perspex blocks ( with curtains). It remained at proposals.

For example, he offered to damage cars for a fee of F 25.- for an ordinary and F 100.- for a luxury treatment. So he presented a series of suicide projects: electric shoes. Vaginas and penises in his all-gold showroom on Amsterdam’s Prinsengracht canal.

Pieter Engels could also be summoned for some time as the man who, with a golden saw, sawed the legs under the chair of whoever wanted it. In New York, as he did recently at the Middelburg World Stage, he worked on future projects.

For example, he was working on the Godfinder machine to be put into operation in 2889, programmed dance shoes very suitable for the coming century, the nail that hammered itself into the wall and a tele-transportation machine. Those ‘Inventions ‘ will be compiled in a booklet to be published soon. Pieter Engels: ‘That will be one booklet. The other is called ‘ Engels Formulations ‘ and it is full of two- or three-line texts.

One then:

”the sun sets with maximum indifference”

Andre Oosthoek

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam 1981 Parallel Landscape

PARALLEL LANDSCAPE (’77 – ’80)

STEDELIJK MUSEUM AMSTERDAM January 16, 1981 through March 15, 1981, rooms 24, 25.

” People who know me know that I care very little about styles and don’t try to artificially deal with the same things all the time. Pieter Engels (1938), an artist who is best known for his objects, assemblages, unusual projects and actions, is speaking. When we ask him, somewhat surprised, why he has returned to painting, he says: ‘I actually already predicted it in 1972 at my exhibition in the print room of the Stedelijk Museum. The catalog of that exhibition states:

‘- (after numerous wanderings)

- after numerous ‘uses ‘ resp. discoveries of known and unknown ( or known and unused) media in the visual arts (O.A.) outside of ‘orthodox’ painting,

- it is not impossible,

- that Engels ( presently and or future) closes the vicious circle (action – reaction, reaction – action, etc.) ( briefly), (briefly): (also means temporarily) by once again using the medium of painting that has (presently) become new to Engels. “

According to his official biography, Engels stopped painting in 1963. “That in itself was and is not enough for me, since my interests (can) go out to basically any visual medium. That is also the reason why I stopped painting earlier. Then, in 1974, I had that phase of painting in the dark. With that I wanted to deliberately eliminate the virtuosity-the choosing of the place of your brushstrokes within a frame, balanced compositions, beautiful brushstrokes, color, so-called laws, etc.’ In a totally darkened studio, everything there was painted black including the canvas, Engels worked with all the colors of the rainbow, without being able to see in the dark which tube he picked up. ‘The most perplexing thing for me was that for the first time I experienced an image as any observer would see it. You turn on the light and…Bam! The image is there. When you just make a thing, you see it from the first stage to the last stage, and so for the first time I saw it right off. They were also always right for my liking, there was nothing wrong with them.’ The series of paintings he is now showing is in black – white, because Engels, as he says , is primarily about a pure painterly act, derived from the movement of a landscape. ‘Black – white is a very pure form of expression, it is very minimal and therefore for my feeling also much more expressive….I find when you look back in history, drawings also always much more exciting.’ These works are a result of activities during his summer vacations in the south, where, having had enough of lazing around and sitting on terraces, he began drawing landscapes again. ‘When I started it was just about the activity, I didn’t want anything with it really. I just sat and scribbled straightforwardly. Only intimates knew I was working on it and they said, Pieter is making a shadow oeuvre.’ The paintings are very orthodox, classical landscapes with sun, sky and foreground. The only thing different about them is the black bar that hangs below them with the sign ‘Parallel Landscape’.

Engels : “I think that bar is necessary, perhaps as a kind of connecting sign to other things, to the outside world. That beam has the function of kicking in an open door. Everyone knows that a painted image is in fact just paint and not a landscape at all. A painted image is a parallel reality or the “portrait” of itself. (Margritte: a painted pipe is not a pipe).’ ‘ An essential part of my work is that I always involve the viewer (because without a viewer there is no work of art, another open door). By using text, among other things, I talk to the viewer, as it were. Such a bar of text gives the viewer something to hold on to or, on the contrary, he slips on it.’

When Engels recently showed his new work for the first time at Orez Mobiel in The Hague, some artists were very surprised; they had to get used to it. And then, he says, they choose a work like (Dilemma) The Painters Painting is never on the canvas, because they find it typical of Pieter Engels. ‘And of course it is.’ Engels: ‘Because of the art market, many artists have become afraid of experimentation, because once they get on their high horse they can fall on their face, since they don’t answer to their ‘trademark’, for example. Or they suffer from the originality syndrome, according to Engels also a disease of our time, when at a certain point expressions of totally different people in very different countries can run parallel. ‘And all those trends that are stroked by museums and critics. That whole international art criticism often has a kind of Albert-Heijn mentality, they run after everything, terrified of missing the latest offer. Especially if new techniques are developed at a certain point, such as video, for example, they receive a great deal of attention and appreciation. This is followed by a craze of, oh, people are painting or drawing again. Nonsense, every medium is a medium that you can handle. A statement like ‘the time of the easel painting is over’, which Sandberg made in the early 1960s, was therefore ridiculous.’ Isn’t Engels himself participating a bit in these fashions by suddenly starting to paint again after all this conceptual art, or is this his commentary on this new craze? I think that at a certain moment there is a common feeling about a number of things. For example, in the last five or six years, things have happened in the conceptual direction that have become so dry, especially by epigones of epigones, that you say: now let’s get away from thinking (or actually not let’s get away from thinking because every thing originates from a concept).

(Tijmen van Grootheest, Din Pieters, Joost van de Pol)

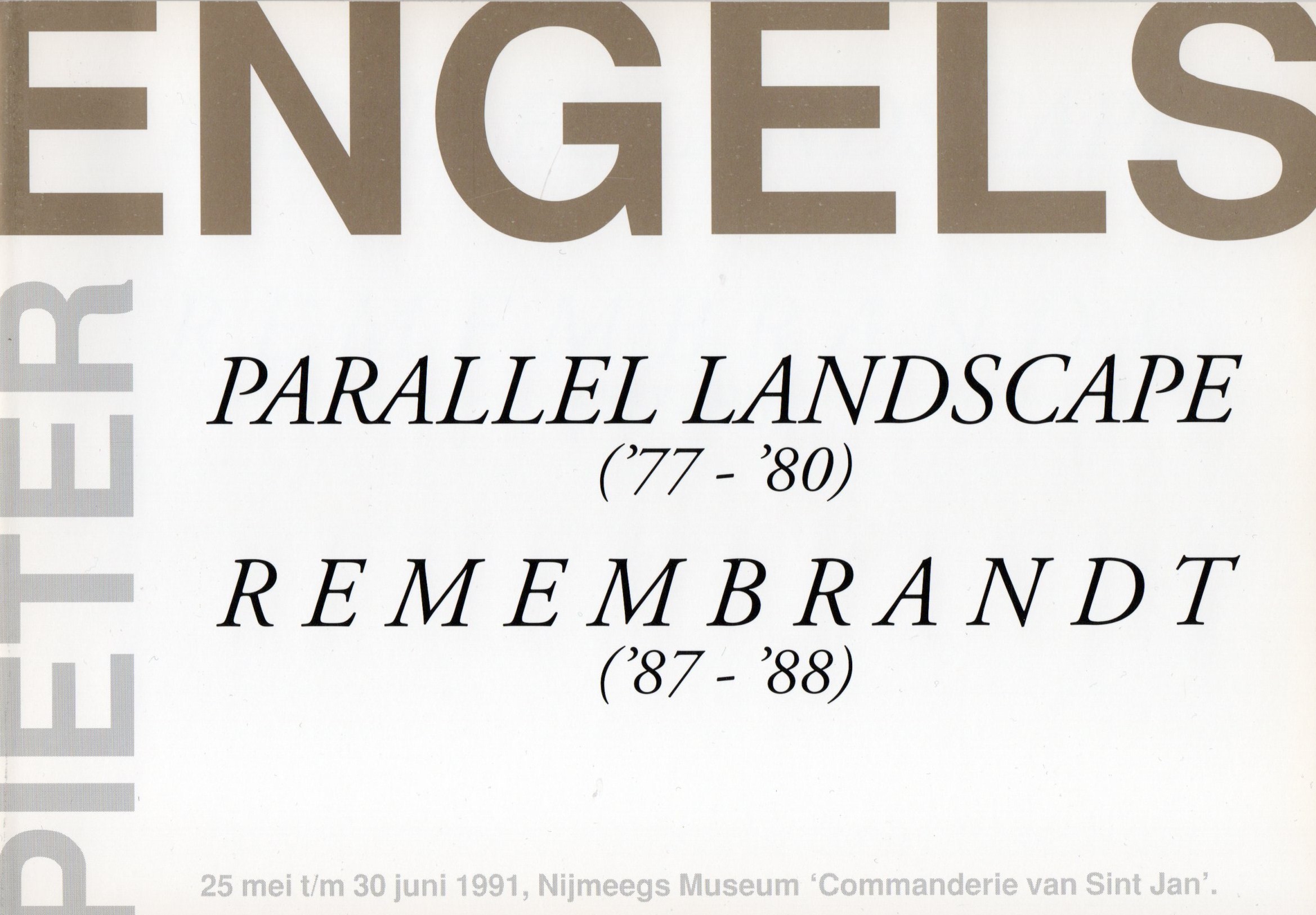

MUSEUM DE COMMANDERIE NIJMEGEN 1991

THE IMPULSIVE SIDE OF THE WORK OF PIETER ENGELS

“The exhibition of two phases from the total structure of the oeuvre of Pieter Engels, as the art world has known it for about thirty years now, does not aim to show a development and of course even less to provide an overview. Rather, it provides insight into two special constellations that have arisen in the course of the career of the now 52 – year-old artist. His biography is characterized by coming from a very artistic family – his father with the same name was an exceptional artist in the Brabant painting of his time – and an early maturity. In 1968 Jean Leering presented at the “Documenta 4” exhibition several works that caused a stir because of their position in the border area of concept art and object art, where the viewers of the time simply had an eye for only one side of Engels’ dialectic. In this dialectic, calculation and improvisation are applied in such a way that one might suspect a somewhat detached attitude full of laconic irony on the part of the maker. But this touches only one of the two main motivations of the artist. If one were to ask him whether he attaches the greatest importance to this, his answer would probably, in all conscience, be affirmative. Pieter Engels feels the need to view his work through glasses that provide him with a skeptical distance. This does not detract from the coherence and integrity of his oeuvre. This distance from himself does give him the freedom to follow an unsuspected impulse. This results in works in which the hand and the mind are no longer strictly controlled, so that they can relax and develop. This is how the other side of his work emerges. This has been present from the beginning, as shown by the large ink drawings from the early 1960s, which made significant contributions to the informal painting of the time, as can be seen in retrospect. The connection with the works from the phases discussed here is easy to point out.

These phases are not unrelated because they both refer to the same starting point to which they in a sense pay homage. When the first impulse, emanating from well-nigh unintentional, accidental drawings, took hold, it shocked many. One had no longer thought such uninhibited landscape painting possible. Engels himself described in a conversation at the time how the barriers within himself had collapsed one by one. The hand going back and forth across the sheet with a blunt knife, whose blindly engraved trace only materialized into landscape after the brush full of ink was stroked over it, ( the flowing ink fills the grooves of the knife) is a moment in which the responsibility of the mind has been abandoned. Landscape is thus the theme of the one phase. No topography is evoked, nor is the arsenal of classical scenery used that so often determines the conventions of landscape painting. Rather, far-reaching gestures on the usually large sheets of paper summarize a few forms: horizon, sky, structure and vegetation. The omission of all extraneous matters results in a grandeur that puts the eye’s habit of searching for details out of action. It evokes memories of the sketchy, hand-sized landscape drawings of Rembrandt or Van Goyen, but here we are dealing with lapidary landscape images in hundredfold magnification. The dark undergrounds continue to blossom even in the now following phase of transposition on of white and light gray brushstrokes. The effort to maintain the tight yet open formula of reduction of the form apparatus is evident to the viewer. The large form remains intact thanks to broadly spaced, wide-ranging swaths of chalky, pale paint on the black of the ground. But in addition, these semi-monochrome paintings show just as much of a wide variety of loamy valences that arise almost naturally because the non-spatial ground, which guides the entire painting process, penetrates the light color in every possible nuance. The white becomes opaque and opaque only when it stands pasty on the black ground. All light, loose, sketchy movements activate the action of the fond and in this way enrich the painter’s instruments, so that monochromy is interspersed with seemingly coloristic valences, so that the renunciation of all other colors, which are strictly adhered to, hardly seems important anymore. The second phase of our exhibition, which, under the general title “Remembrandt”, portrays the memory of a contemporary painter of Rembrandt, who became the father figure of Dutch painting of the Golden Age, pays no attention to the monochromes. Again, landscapes are featured, but this time on a white ground, both in the large paper strips for charcoal drawings and gouaches and also in the canvases. And it does not stop at general allusions to the style, composition and typology of the old master, but to each work individually. For in addition to the landscapes, many group and individual portraits are discussed, which form part of the art lover’s regular repertoire of commemorations.

They are portrayed in the form of pictorial variations that have sprung entirely from Pieter Engels’ brain. A few main accents are put on the canvas with a broad brushstroke, which are then reinforced by painting over them more than once with thick liquid paint. Many parts of the picture plane provide a quieter accompaniment to this. The gestural work concentrates on the main brushstrokes that the longer one studies them, the more clearly they refer back to the work of Rembrandt. The physiognomic elements are often strongly exaggerated, yet no caricature is created. To speak of an ‘Altersstil’ in Pieter Engels, of a style that characterizes him in his old age, he is still too young at 52, but perhaps it should be pointed out that the old Picasso handled images in a similar way that mobilized his pictorial powers of reflection. Rembrandt also plays a certain role in these works. With Picasso’s style of painting, Engels’ shows no similarity. His impasto, Engels’ way of applying paint thickly, is not found in this form by anyone else and, moreover, in its double signature of Brabant and Dutch characteristics, it is unmistakably Dutch. As a painter with a critical distance to his own image and as a teacher with years of experience (at the Royal Academy in ‘s-Hertogenbosch), Engels can always decide for himself when, where and to what extent he will let go of the reins. Openness and control remain in balance. The concentration of the color palette on just a few, related colors simplifies the process of creation and preserves the result from the commonplace pleasant coloration, which the old example had always avoided. In a situation where contemporary painting seems to have cast aside many elements of classical aesthetics, the paintings and drawings of Pieter Engels offer points of orientation for painting in the true sense. Moreover, they support the thesis that one does not necessarily have to cynically relativize in order to open up perspectives for the future of painting.”

(Hans van der Grinten,1991).

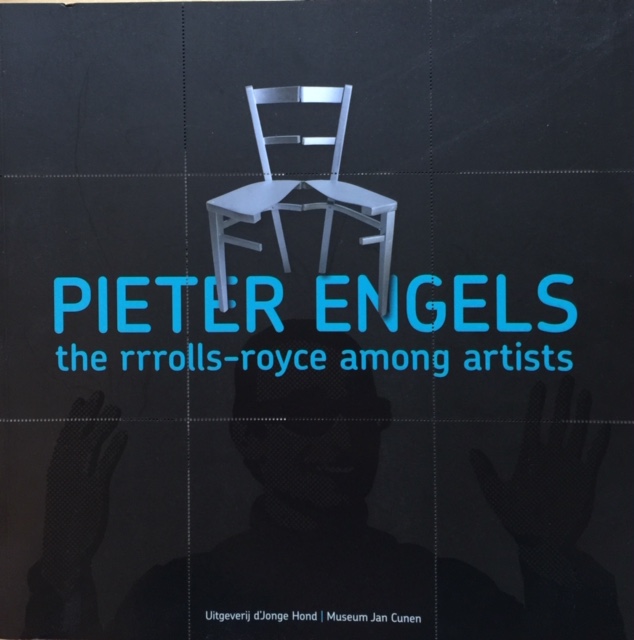

Museum Jan Cunen 2010 Pieter Engels the rrrols- royce amongst artists

Stylelessness

“One of the most striking and most common characterizations in the reflections on the work of Pieter Engels from the 1960s and 1970s is the emphasis on the ‘stylelessness’ of Engels’ work. Or, as art historian Carel Blotkamp beautifully put it: His activity as an artist seems to be aimed at undermining the concept of style. Style, in the sense of a fixed mode of expression, use of fixed means and a fixed repertoire of images, has been a natural attribute of the artist since the Renaissance, and Engels recognizes in it the danger of mistaking style for personality and consequence for quality, a danger that is greater than ever in the twentieth century because of the commercial need to consolidate a style once acquired. Engels’ weapon is the quotation, the paraphrase, sometimes the parody. Also in the catalog of the exhibition The Selfportrait of this century that took place in Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in 1975, the chief curator, Renilde Hammacher, gave an art historical introduction about this striking stylelessness and came up with examples of great artists of the twentieth century who also used such a hybrid method, such as Francis Picabia (1879 – 1953). Marcel Duchamp and Bruce Nauman. It is as if the curator felt compelled to justify this “stylelessness” to the public. The fear that these inconsistencies by Engels would be interpreted as an offer of weakness comes across as rather dated in 2010. Nowadays, art lovers are no longer surprised when an artist switches from one medium to another or changes themes or visual language. The idea of a lack of style is therefore no longer really relevant. When leafing through this book, it is striking how much unity in style there has been in his work over the years. His works from recent years have many similarities with EPO sculptures from the sixties. Sculptures that have a clean and businesslike appearance, where text signs form an integral part of the work, which contain little color and where language, deconstruction, reversal and references to art once again take center stage. Surveying over fifty years of artistry, it is rather the unity and cohesiveness of Engels’ oeuvre that stands out, the clear playful, but also focused approach that makes his work so fresh and sharp. It is also not surprising that all his works, however different at first sight, still exude that typical Engels spirit. Engels is an artist who knows very well what he wants and who, despite ( or thanks to) all the jokes and antics, has remained very close to himself. In his life he has never joined a movement or collective, he has always gone his own way. When we look back at his still expanding oeuvre, we cannot help but conclude with Simon Es: WHAT ENGELS DOES ENGELS DOES WELL!”

(Fleur Junier, 2010, PIETER ENGELS the rrrolls-royce amongst artists, page 40)

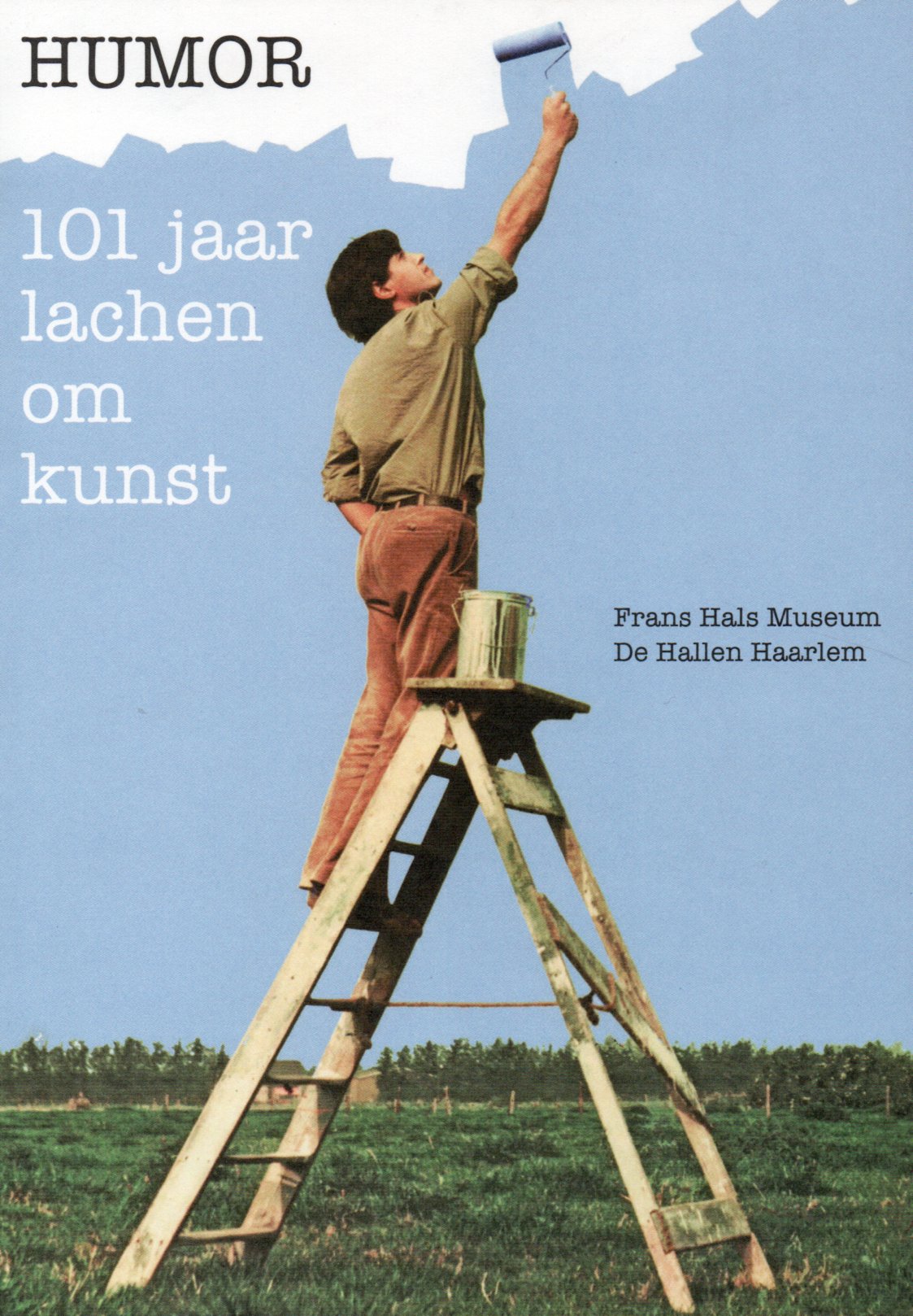

FRANS HALS MUSEUM – DE HALLEN HAARLEM

101 YEARS LAUGHING AT ART

” We want to incite, topple, to bluff, to tickle, to tickle to death, to be muddled without coherence, fighters and negationists. This bold statement does not come – perhaps fortunately – from the compilers of this exhibition but rather from the German multi-artists Hugo Ball and Richard Huelsenbeck. These gentlemen and their kindred spirits turned the official canon of art on its head during and after WW1, with disruptive and disorderly actions under the label of ‘dada’. Actions that felt like rushed stages in a search for new paths for art. Against the times and distinctly contradictory. Actions that continued to resonate long after dada and have a very lively Nachleben in Europe and beyond. The exhibition, of which this book is a part, traces systematically on the one hand and deliberately hopping and skipping on the other, the humorous traces that dada has left in recent Dutch art history over the past 101 years.

This tracking is paradoxically a serious undertaking. During the preparation of this exhibition, the anonymous creators of the satirical website FC Kunst pointed out to us that an exhibition charting ‘humor in art’ had to be a very lame if not downright bad joke. Clearly, this exhibition is not a farce or harlequin in which drollness and farcicality are central. There may be the occasional laugh, but the exhibition shows and senses that jest and seriousness often go hand in hand with artists. If it illustrates one thing, it is perhaps that dada was essentially a torture device for art, a rack on which art was stretched on all sides and tested for its flexibility. The real legacy of dada, as curator Antoon Erftemeijer points out, would thus consist of the fact that since the Dadaists’ exploration of the boundaries within art, just about anything is permissible and no possibility is excluded.

Stretching and extending are also code words in and for the series of Summer Exhibitions to which this presentation belongs. The starting point of this series is always the museum’s own collection of modern art, which is supplemented in various ways and extrapolated in a movement that extends from Haarlem to beyond the city boundaries. Dada, after all, was an international phenomenon but also took root temporarily in the Spaarne city with, among other things, a legendary performance evening on 11 January 1923, described in detail by W. de Graaf in the publication ‘In Haarlem I blow my nose see Schwitters me’.

Dadaists are said to be rebellious and rebellious, they agitated with new mixed forms against the ‘old’ established order of art and the acknowledged greats of art history. As a tribute to this (un)appropriate irreverence, this time we are not only showing work in De Hallen but also in our location at the Groot Heiligland, the Frans Hals Museum. Parodies and caricatures of well-known, iconic works of art are on display. In this way, awe for tradition and masterpieces is coupled with Dadaist tickling and churning. Dadaists, in addition to being a – dogmatic, were also seen as boundless. In this spirit, the exhibition extends beyond the walls and halls of the museum. Indeed, this book is accompanied by a quartet game that you can collect yourself during your tour of both museums and use to give a new and perhaps unorthodox paper form to this exhibition at home in the club chair or at the table.

Dada, moreover, was a DIT – Phenomenon (Doing It Together) in which collective action and close collaborations often predominated. This also applies to this exhibition. Also on behalf of the curators of the exhibition, I would like to thank the museum team, designers Mart. Warmerdam and Chantal Hendriks, museum and private lenders, and artists who have collaborated on this exhibition, and especially to remember the Van Toorn Scholten Foundation for their generosity, trust, and exclusive support of this exhibition.” (Ann Demeester ,2017,Humor 101 years of laughing at art, pages 1 and 2.)

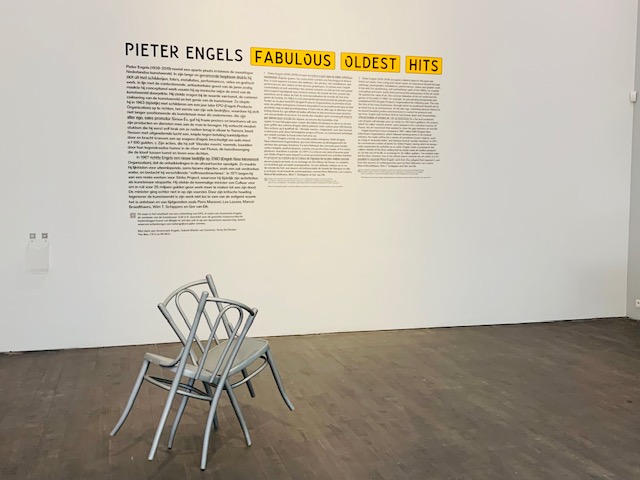

SMAK GENT 2023

PIETER ENGELS FABULOUS OLDEST HITS

S.M.A.K. presents a condensed overview of the Dutch conceptual artist Pieter Engels (1938-2019). A separate room will present works by his contemporaries. Pieter Engels (1938-2019) occupies a distinct place in the post-war Dutch art world. In his long and varied career, he expressed himself with paintings, photographs, installations, performances, video and graphic work.

In line with the contesting, anti-authoritarian spirit of the 1960s, he made conceptual work in which he ironically punctured the seriousness of the art world. He questioned the value of art, the commercialisation of the art world and the genius of the artist. In 1963, for instance, he quit painting (temporarily) to found EPO (English Products Organisation) a year later, the first of his many businesses, positioning himself no longer as an artist but as an entrepreneur.

As his alter ego, marketing director Simon Es, he issued beautiful posters and brochures to market his products and services. He sold pieces of furniture that he first broke himself and then reassembled, offered bottles of exhaled air, cut through banknotes for a fee and scratched cars (Engels damages your car nicely for f 100). His actions, which he himself called ‘Wonder events’, were bathed in the atmosphere of Fluxus, the art movement that sought to close the gap between art and life, through their contrarian humour.

In 1967, Engels founded a new company, ENIO (Engels New Internment Organisation), which followed developments in the funeral industry. For instance, he made coffins for a variety of sometimes bizarre objects, such as a bag of drowned water, and devised several suicide machines.

In 1971, he started working on a series of works for Strike Project, for which he temporarily ceased his activities as an artist. He proposed to the then culture minister that in exchange for 25 million guilders, he would not make any more works until his death. However, the minister did not accept his proposal. Because of his critical attitude towards the art world, his work cannot be separated from the zeitgeist in which it was created and from contemporaries such as Piero Manzoni, Lee Lozano, Marcel Broodthaers, Wim T. Schippers and Ger van Elk.

The exhibition is complemented by a room with works by Dutch conceptual artists, such as stanley brouwn, Jan Dibbets and Ger van Elk, from S.M.A.K’s collection.

The expo is the result of a donation from EPO, in the name of Annemarie Engels, the artist’s widow. S.M.A.K. has the largest museum collection of contemporary art in Belgium and is therefore committed to a dynamic recruitment policy of which donations are a more important pillar.

Thanks to Annemarie Engels, Galerie Martin van Zomeren, Anny De Decker, Flor Bex, CKV and M HKA.